Biography

Russell Manning Vifquin Jr was born on April 1, 1918 in Ames, IA. He was the first of four children born to Iowa State Professor Russell Vifquain and his wife, Zola. Professor Vifquain was in the College of Agriculture in agronomy and later directed short courses for working farmers wishing to learn new methods. The family lived west of campus at 524 Forest Glen in a wooded area that was a great place for active children to grow up.

Russ Jr. came from a distinguished military line – his great-grandfather, Victor Vifquain, was a Civil War general from Nebraska who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his efforts to kidnap Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Russ Jr. soon became the adored older brother to Bob, Ned and Elaine and showed his leadership and athletic interests early. In 1929, in 5th grade at Welch School, he won 1st place in the 80 pound category at the All City Grade School Wrestling Championships. As a boy growing up, he delivered papers, trapped animals along the river and caddied at the golf course. Since there was already a Russ in the family, he was nicknamed, “Juny” – short for Junior. Later, friends and Army buddies called him “Vif”. Russ was a leader in the family and his friends were always at the house, hanging out. Sister Elaine was 10 years younger and Russ took care of her – he gave her her 1st pair of nylons and a gold bracelet.

In junior high he played football and in high school was homeroom secretary and active in Hi-Y, Dramatics, “A” Club, Varsity Club and intramurals. He played football but developed his real skills on the golf course. He was on Ames High’s 1st golf team and was a medalist his junior and senior years. In 1934, he won the Ames City Golf championship. The Ames High golf team on which he played won the conference championship the spring of his senior year over four other schools. The margin was 25 strokes and the team was “so far out in front the outcome was never in doubt.”

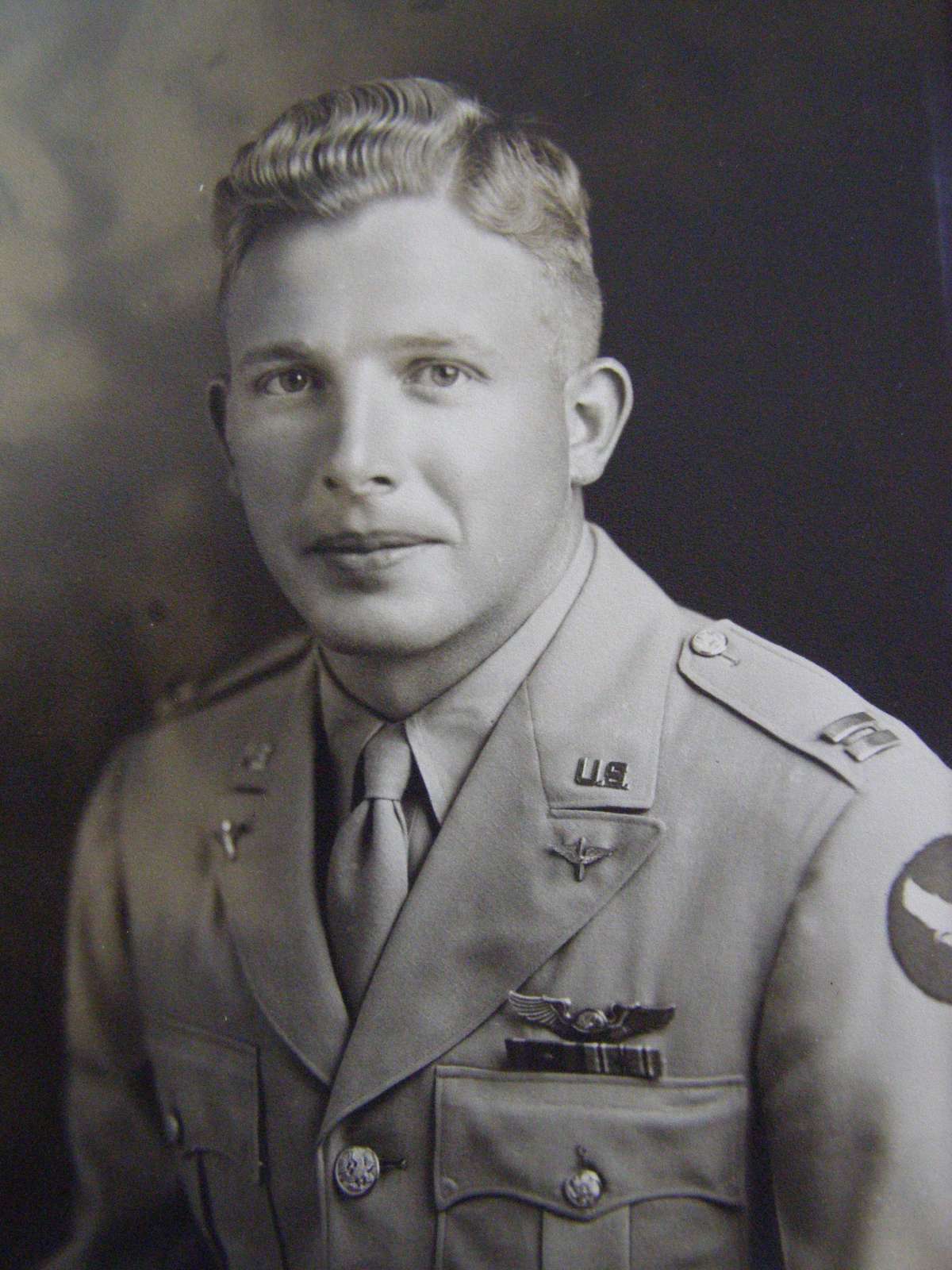

As a young man, Juny was blue-eyed, sandy-haired and stood about 5’ 8”. He graduated from Ames High School in 1936 and entered Iowa State College that fall in engineering, pledging Phi Delta Theta fraternity. At Iowa State he continued playing golf and in 1939, was a member of the Big Six golf championship team at a tournament at Wakonda in Des Moines. Juny was a medalist in the 1st round and was referred to as the “blond demon of the fairways.”

In the spring of 1940, with the uncertainty of war and being drafted, Russ left Iowa State and volunteered for the US Army Air Corps. On May 9 he was inducted at Santa Maria, California where he did basic training. In August he was assigned to Miami, Florida and at Coral Gables went through a 12-week school in Celestial Navigation at the University of Miami. Russ was in the first class of navigators to be trained by Pan American Airways for the US Army Air Corps. He was schooled in aerial navigation and weather forecasting. He was one of the first 44 cadets to finish at the school that eventually trained 850 navigators. After his November 1940 graduation, he headed home for a visit and then went to Salt Lake City for six weeks of flight gunnery training.

In April 1941, he was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant and in June, shipped to Gowen Field in Boise, Idaho to train on the new B26 “Marauders”. While in Boise, he played in a note-worthy golf tourney where he defeated the defending champ in a big upset and carried off a large trophy and prize golf bag.

In November 1941, he was ordered to the South Pacific to rush B17s to the Philippines. A letter postmarked Dec. 19, 1941 said, “Left Boise Friday evening, by airplane, for Hamilton Field, CA. [Am] assigned to the 32nd bomb squadron. They are heavy bombardment and we are flying the latest flying fortresses, B17-E. Hamilton Field was the meeting place for everyone, all those heavy bombardment groups located around the west coast. Our plans at first were to go to Manilla and disperse again from there.”

With the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec, 7, 1941, his orders were cancelled and he was re-routed to Alaska in the first B26 bomber group. During WW2, Alaska was “one of the most strategic places in the world.” The Aleutian Islands offered the most direct invasion route to the heart of Japan - from San Francisco to Japan by way of the Aleutians is 1700 miles shorter than by way of Hawaii. The islands are a series of sunken volcanic peaks, separated sometimes by 100 miles of open water. Temperatures there seldom get down to zero, so the treeless islands are often shrouded in fog. Winds howl day & night and weather conditions change suddenly.

In January 1942, Russ arrived in Alaska and in May was promoted to 1st Lieutenant. His squadron was among the first to land and operate from the advanced base on Adak Island in the early spring of 1942. He spent 18 months in Alaska and during that time, flew 30 bombing missions through bleak, frigid and foggy Alaskan weather.

Two of the islands, Attu and Kiska were occupied by the Japanese. Flying conditions were bad year around and regular bombing missions were nearly impossible because of fog. Air crews found there was lots of waiting.

Letters from Russ in February 1942, said “Our activities are still somewhat limited. Guess we won’t get too much of a work out unless someone tries to attack. We are biding our time, more or less, and waiting for something to happen. Frankly, I can’t see anyone starting anything up here but we are ready in case they do. …. “Always have to hesitate a moment when I start to put down the day or date. Every day is so much the same it’s not hard to get mixed up. Am sitting in squadron operations writing this, ready to take off in a moment’s notice. We run schedules on alert duty and about half our time is occupied by this.” Another letter said, “Has been rainy the past few days so haven’t done much flying. Mostly sit around and play cards, read and sleep.”

In a revealing letter to his brother, Russ stated, “People are beginning to realize that flying isn’t glamorous and I would personally say it was anything but. Just another job and rather rough at times. My only [wish] is that this whole business ends as soon as possible [so] I can live a normal life again. Funny how at a time and situation like this, one thinks about the so-called “simple things in life” and how much he didn’t appreciate them, [like] the chance for a home cooked meal, fresh milk, a woman’s voice, wearing civilian clothes or saying what you like in a letter and a thousand other things.”

But despite poor conditions, bombing raids did occur. One pilot was quoted as saying, “We don’t think it’s too thick until you can’t see your co-pilot.” Russ participated in a June 4, 1942 attack against enemy naval concentrations that received heavy anti-aircraft fire. He received his first air medal for that raid. But the intermittent raids did little to unseat the well-entrenched Japanese.

A letter dated Dec. 9, 1942, said “They are playing White Christmas on the radio and if anything will make you homesick, am sure that will do the trick.” Russ got to go home for Christmas 1942 – a happy time for the family.

In March 1943, Russ was promoted to Captain and decorated with the first Oak Leaf cluster to his Air Medal for bravery under tough flying conditions.

The next month in a letter home, noting his birthday, he wrote, “Don’t know whether I feel a year older or not - but am sure that the past 12 months won’t soon be forgotten. Do believe more has happened to me in the past year than in any other - but only hope I can get through the coming ones in as good shape. In May 1943, Russ’s 77th Bomb Squadron was sent back to states to rest.

Alaska footnote - about a year after Russ left, Attu was taken by the Allies, allowing regular bombing of Kiska. In August 1944, the Japanese suddenly evacuated Kiska under cover of fog, their last stronghold in Alaska. Bombing destroyed their radio and cut off communication. The Allies took over an airfield, submarine base, weather and radio station and a harbor bigger than Pearl Harbor.

Back in the states, Russ was assigned to Barksdale Field, Louisiana; then Colorado Springs, then Will Rogers Field, Oklahoma and in December, he landed at Esler Field, California. At this time, he was eligible for a discharge, but was nominated to join the B29 Super-Fortress group and he volunteered for an extra tour of duty in the Pacific. He trained in Salina, Kansas.

On November 18, 1944, Russ went from Hawaii to Saipan in the Marianas with the first B-29 group. The B29s were “the mightiest aerial weapons of WW2” designed to fly very long distances to attack the Japanese homeland. Russ was elated to go with these planes. They were equipped with armor, leak proof fuel tanks and heavier guns. Speeds of 300 plus mph could be reached and the planes could operate in excess of 1,000 miles at sea.

Barely a week after he arrived in the Marianas - on Friday, November 24, 1944 - the 21st bomber command launched the first of many daylight bombing missions over Tokyo industrial sites – a 3,000 mile round trip. Navigation was extremely difficult and the men who guided the huge machines had none of the visual “fixes” available to navigators who fly over land.

These were the first raids on Japan since Jimmy Doolittle’s attacks in April 1942. Aircraft manufacturing locations were hit and the B29s received little anti-aircraft fire due to the high altitude and speed of the B29s.

On that raid - November 24, 1944 - the B29 navigated by Russ made it to Japan but limped 1,500 miles home on two of its four engines due to mechanical difficulties. This feat was hailed as “a magnificent achievement” as two engines were never designed to fly that kind of load. To keep the plane in the air, the crew stripped the interior and threw out parts all the way back to their base, where they made an “uneventful” landing. It was the first time a B29 had flown so far on two engines. Pilot Lieutenant Colonel George Sheahy credited Vifquain’s accurate navigation as chiefly responsible for the safe return.

In a letter, Russ said, “Yes, our first mission [was] quite an experience. It’s a fine crew and when the chips were down, really proved themselves. However, never any doubt in my mind that we’d make it back okay. One way or another...Our operations to date have more than met expectations and I only hope our good luck holds out.”

On March 9, 1945, Russ was on his 4th raid over Tokyo. His B29 was one of 343 Superfortresses assigned to firebomb Tokyo from close range – just forty-nine-hundred feet. Great damage was done to the city – but it did not deter the Japanese will to continue the war – so more raids were mounted.

On his 27th birthday, April 1, 1945, Russ was promoted to Major and later that month, received the 2nd and 3rd Oak Leaf clusters to his Air Medal.

In what was to be his last letter, written May 12, 1945, he said, “They have set up a new training center for B29s at Tucson and guess it has developed into a big project. Think a desk job there would suit me fine.”

On May 14, 1945, Russ prepared for his 17th B29 mission. He was to be the lead squadron navigator for five hundred B29’s – an indication of his reputation as a navigator. There was no mechanized navigation equipment -- everything was done by sextant and it took 45 minutes or more to tabulate a course.

The mission departed from the Marianas at midnight for the 5 ½ hour flight to Nagoya, Japan. Russ’s B29 had early indication of trouble in the #1 engine during the first climb to altitude, but the plane made 16,000 feet and proceeded on. About 25 miles inland, #4 engine malfunctioned. The plane left formation and ditched its bombs – but one hit the bay door and it could not be closed. Conditions on board were serious.

Russ was able to establish their position as being about one hour’s flying time to the tiny island of Iwo Jima, southeast of Japan. Iwo was taken from the Japanese only two months before and converted to a strategic US base. The crew did not expect to be able to keep the plane aloft to fly the 700 miles. Because of weather conditions, accurate navigation was all but impossible. But according to a crew mate, Russ did a “miraculous” job of pinpointing Iwo. As he said, “With any other navigator, none of us would have made it that day.”

Clouds were low and visibility poor. Attempting a landing was ill-advised, so the commander gave the order to bail – hoping to do so over land or near a destroyer. Radio contact was made at Iwo Jima. Then the #3 engine malfunctioned – but the plane limped on. When the #1 engine caught fire all were ordered to bail. It was about noon.

The usual bail-out is 5,000 feet and they were lower than this. Twelve were on board and all bailed, with the plane exploding 10 seconds after the last man was out. Russ left the plane through the forward wheel well and crew members thought he cleared the plane. The clouds were so thick crew members could not see one another and could not see if they were over water or land.

Two ships in the area were alerted. Some crew landed on the island, others in the water at various distances up to seven miles from shore. Ten were picked up. Two others that landed in water were lost – Russ Jr and the tail gunner, Don Barnes. Rescue vessels searched for 48 hours before, during and after the storm that rolled in, to no avail. Russ was eventually declared dead and May 15, 1945 was recorded as the date. His body was never found.

“Dick Budington, the radar operator, wrote, “Vif and I had lived together in Salina and all the time we were overseas and had flown most of our missions together. Our work also in group operations was very closely allied and this long association, added to the catalyst of a series of rough missions together, built up a friendship that is common only in time of war. Vif was my closest friend out here and I owe my life to him – together with the rest of us who were picked up.”

Russ’s family was devastated, and hoped against hope that Russ would be found. Three months crawled by. The war ended. The reality of the situation became clear: their Juny would not be coming home. Elaine never thought anything bad would happen to Juny – he was so handsome, good looking and strong.

For many reasons, no memorial service was held in 1945 so this ceremony - 65 years later is the first time Russ’s story was told and his life honored.

Russ is remembered with a headstone at the Ames cemetery and is listed on memorials in Hawaii’s “Punchbowl”, at Ames High School, on the Ames Veterans’ Memorial, at ISU’s Alumni Center and Olson Athletics Building, and of course, here at the Memorial Union.

Russ’s story and those of all the members of that first 1940 Navigation School class have been recorded in the book, On Celestial Wings by class member and former Indiana governor, Colonel Edgar Whitcomb.

In addition to his Air medals, Russ was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, the highest award given to a member of the military after the Medal of Honor.

The Purple Heart was awarded posthumously, accompanied by these words from President Harry Truman, “Major Russell Vifquain Jr. stands in the unbroken line of patriots who have dared to die that freedom might live and grow and increase its blessings. Freedom lives and through it he lives in a way that humbles the understanding of most men.”